July 2021 Science Corner | Fire, and the legacy of indigenous land use in the Intermountain West

The Fremont peoples engaged in large-scale land management in this area over centuries, often using fire as a tool to clear land for farming or to cultivate specific species of plants they needed for food or domestic purposes. Now, thanks to the work of an interdisciplinary team of researchers led by Dr. Vachel Carter, the impact of these management activities on the Fish Lake Basin can be measured as distinct from the impact of climate.

Story and interview by: Peter Wyrsch

Interviewees: Vachel A. Carter (lead author), Brian F. Codding

“Legacies of Indigenous land use shaped past wildfire regimes in the Basin-Plateau Region, USA”

Authors: Vachel A. Carter, Andrea Brunelle, Mitchell J. Power, R. Justin DeRose, Matthew F. Bekker, Isaac Hart, Simon Brewer, Jerry Spangler, Erick Robinson, Mark Abbott, S. Yoshi Maezumi & Brian F. Codding

The Fish Lake Plateau of Central Utah is well known for its recreational and ecological bounty, including the state’s largest freshwater lake, scenic montane campgrounds, hikable ten-and eleven-thousand-foot peaks, and the famous “Pando” tree: a single aspen tree estimated to be at least 80,000 years old, weighing in at 13 million pounds and extending over 106 acres. Long ago, the region was also home to a different unusual bounty: maize. During a prehistoric farming period that lasted from 900-1400 CE, the region was under cultivation by the Fremont culture, a distinct, pre-Colombian people who inhabited what is now the modern state of Utah.

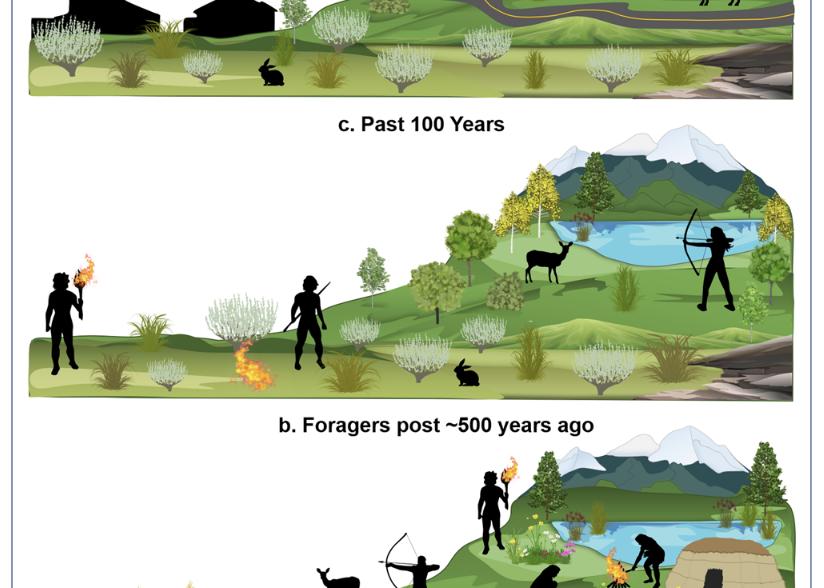

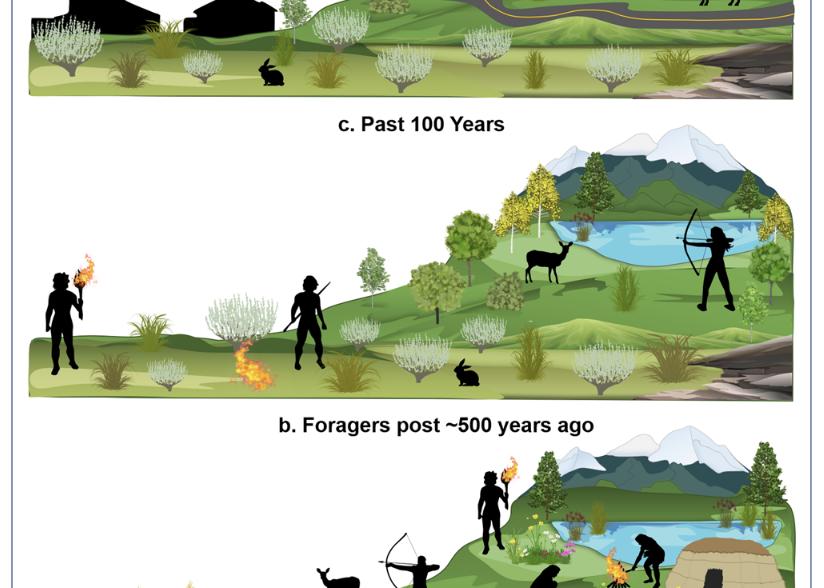

The Fremont peoples engaged in large-scale land management in this area over centuries, often using fire as a tool to clear land for farming or to cultivate specific species of plants they needed for food or domestic purposes. Now, thanks to the work of an interdisciplinary team of researchers led by Dr. Vachel Carter, the impact of these management activities on the Fish Lake Basin can be measured as distinct from the impact of climate. “Lake sediment cores can record anything,” says Dr. Carter. “They’re a really good deposition environment to capture what’s happening in the basin. I’m interested in how vegetation changes over time and how disturbance regimes change.”

When the Fremont peoples used fire as a tool to manage their landscape, they created prehistoric charcoal that settled at the bottom of Fish Lake, along with the pollen and seeds from the native forest. As Dr. Carter describes, “This lake basin has hundreds of meters of mud and potentially has the opportunity to look at climate and vegetation change over millions of years.” And across most of the sediment record, the data were remarkably consistent. The subalpine, mixed conifer forests around the lake burned infrequently, but at high severity. This resulted in predictable layers of charcoal, followed by layers of pollen and seed, followed by another solid layer of charcoal when the forest would burn again, and so on.

However, during the time when the Fremont culture reached its agricultural apex, the record was interrupted by a consistent layer of charcoal. Pollen from the subalpine forest was reduced while pollen from plants used by Fremont peoples increased. “We knew Fish Lake was different because the amount of charcoal preserved in those sediments over such an extended period of time didn’t look like other records from other high elevation sites,” Dr. Carter points out, “where, when they do burn, they burn hot; they burn down to the ground. You typically wouldn’t see an elevated period of charcoal being preserved in a lake sediment. You’d see a pulse and then a valley and then another pulse.”

Armed with these reconstructions and a set of statistical models, Dr. Carter and her team were able to determine that the presence of charcoal in Fish Lake’s sediment was most likely caused by large-scale land management by the Fremont peoples. More to the point, it indicates that people used fire frequently and at low severity to increase the yields of crops they needed.

Dr. Brian Codding, an archaeologist who assisted in the research, is confident in their findings. “There’s no response for fire as a function of drought, but there’s a really strong linear increase in the frequency of charcoal as a function of the number of radiocarbon dated archaeological sites that are occurring on the plateau and in the surrounding area.” This increase in population density meant that there were more communities using fire as a tool to cultivate the land in the Fish Lake basin and, as a consequence, creating charcoal that ended up in Fish Lake. There were simply more people actively burning within the forest to increase the presence of plants they wanted to eat.

This research shows the value of collaboration between researchers in different fields, a fact Dr. Carter is quick to elevate. “If we didn’t use a multidisciplinary approach, we wouldn’t have gotten the answer that we did.” For those who steward and manage western lands, this research indicates the importance of incorporating long-term climate records and archaeological resources into their management decisions. Folks in the fields of forestry & rangeland management encounter archaeology every day; the more you can know about the history of the lands you manage, the better you’ll be able to manage it for future generations.