Exploring the connected histories of forest management and aquatic restoration in the Pacific Northwest

While the histories around legacy logging approaches, fire exclusion, salmon, and changing stream and river health in the Pacific Northwest cannot be summarized in a single blog post, this piece aims to serve as a primer, shedding light on the consequences of historic forest management practices and the need for the ongoing restoration work that Blue Forest is a part of today.

Written by: Signe Stroming, Project Associate

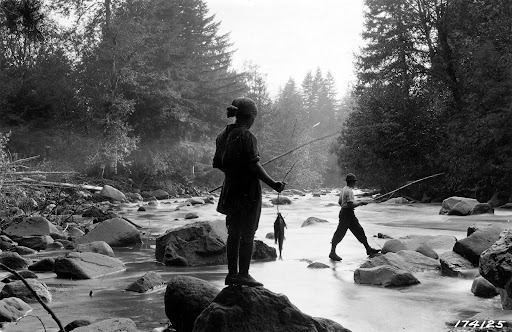

Photos courtesy of: Oregon Historic Society Research Library and U.S. Forest Service NW

Growing up in western Washington, certain dimensions of the landscape, real and imagined, are ever-present. Towering, lush evergreens. Clear and cold creeks and rivers. And, of course, salmon–on school field trips, on my dinner plate, in the news. I knew the broad strokes of how and why salmon stocks have declined far below historic levels: overfishing, large dams on major river systems, conversion of floodplains for agriculture and development, and of course, climate change. Yet, it was not until I joined Blue Forest that I more fully appreciated the profound impact that more than a century and a half of non-Indigenous forest management practices had on not only salmon stocks, but the health of all aquatic ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest.

While the histories around legacy logging approaches, fire exclusion, salmon, and changing stream and river health in the Pacific Northwest cannot be summarized in a single blog post, this piece aims to serve as a primer, shedding light on the consequences of historic forest management practices and the need for the ongoing restoration work that Blue Forest is a part of today.

Degradation: Legacy Forest Management Practices

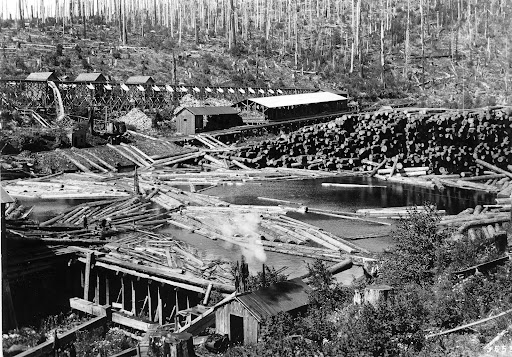

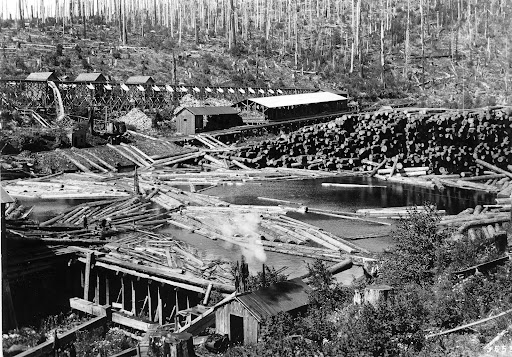

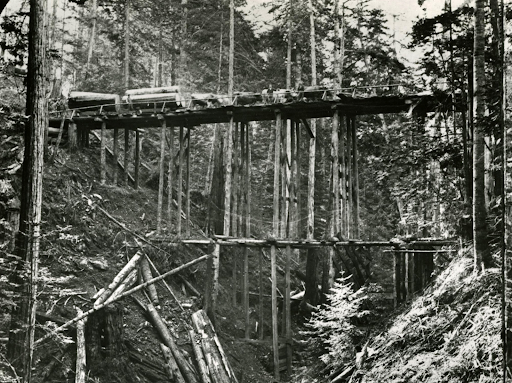

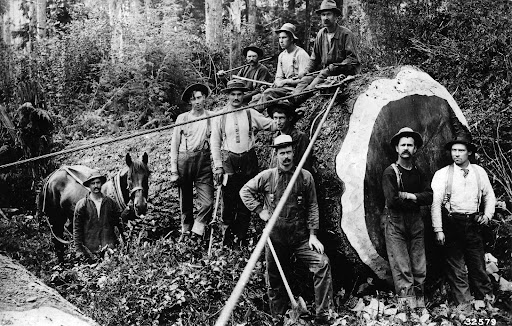

Since time immemorial, Tribal communities have managed both waterways and forests to promote and cultivate animal and plant species that were central to their survival and cultural practices. For Tribal Nations across the region, salmon has always been a staple food source and a critical part of heritage and identity. Indigenous Peoples also used fire to manage forestlands and create conditions ideally suited to edible plants and hunting. However, from the early 1800s, European settlers drove the creation and rapid expansion of the timber industry, which would shape Washington and Oregon’s economic development for more than a century. Fire exclusion, fraudulent land grabs, developments in logging technology, expansion of the railroads, and demand from growing westward expansion facilitated the industry’s growth. By 1910, Washington had become the nation’s largest producer of lumber–until it was overtaken by Oregon in 1938. By one estimate, nearly all the forests in the Pacific Northwest had been harvested by 1995, leaving only 6 percent of trees older than 160 years.

Legacy forest management practices and the magnitude of the logging that occurred have had lasting effects on the health of streams and rivers and the species that depend on them. Logging of large, old-growth trees reduced habitat complexity and biodiversity. Clear-cutting on steep slopes and directly next to waterways increased stream temperatures due to the lack of vegetation providing shade and caused erosion, which led to increased sedimentation in the waterways as well as landslides. Policies outlawing cultural burning and mandating fire suppression changed the composition of vegetation that thrived in riparian ecosystems and reduced the amount of woody debris that found its way into streams. For a period of time, it was common practice to deliberately remove wood from streams, depriving juvenile fish and other aquatic species of important shelter and shaded habitat. Many meandering streams and rivers were also deliberately straightened or “channelized” to secure land for other uses, which further degraded aquatic habitat by speeding up the flow of water, scouring streambeds, and incising the stream channel below surrounding land. As logging trucks replaced railroads, the timber companies and land managers built more and more roads further up in the watershed–the USDA Forest Service even became the country’s most active road builder for a period in the 1970s. More roads contributed to erosion and stream sedimentation. And, when these newly constructed roads crossed smaller waterways, culverts were constructed to maintain the flow of water and prevent flooding. As we now well understand, these culverts often act as fish barriers, fragmenting stream habitat and preventing salmon from reaching their spawning grounds upstream.

It wasn’t until the mid-to-late 20th century (not that long ago!) that our understanding of these systems and our management strategies started to change. Better science, policy directives, and activism have shaped–and continue to shape–management of riparian and aquatic ecosystems in the Pacific Northwest today.

A growing scientific appreciation of the importance of old growth forests for healthy, functioning ecosystems as well as environmental activism in the Timber Wars led to the development of the Northwest Forest Plan in 1994. While much of the Plan provided management objectives for old growth forests in the habitat of the endangered Northern Spotted Owl, it also created an aquatic conservation strategy (ACS) to preserve and restore watershed ecosystems. In addition, the Northwest Forest Plan established 2.6M acres of “riparian reserves,” or protected buffers along streams, lakes, and wetlands designed to enhance habitat for riparian-dependent species, promote water quality, and connect watersheds on the west side of the Cascades in Washington, Oregon, and northern California. The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management also issued joint management strategies known as PACFISH and INFISH in 1995, which established similar protections around riparian habitat on federally managed lands for the eastside of the Cascades.

Advocacy from Tribal Nations and communities continues to shape restoration of aquatic ecosystems, particularly in Washington state. In 2001, twenty-one Tribal Nations in the Pacific Northwest sued the state of Washington, arguing that the state is on the hook for repairing or replacing culverts that have impeded salmon runs in order to meet its obligations to preserve Tribal fishing rights. After almost two decades of legal processes and appeals, in 2018, the Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s decision in favor of the Tribes. Washington must remove and replace over 600 degraded and undersized culverts on state-managed lands to open 90 percent of blocked habitat by 2030.

Restoration: Achieving Forest and Aquatic Ecosystem Health Today

Today, much of the work of the Forest Service, the largest land manager across Oregon and Washington, and its partners across the region is aimed at restoring riparian landscapes and aquatic ecosystems and undoing the legacies of logging and unhealthy forest management. Of the more than 25,000 stream miles in Oregon and Washington that are designated as “critical habitat” for Endangered Species Act-listed species of salmon and trout, almost 6,000 of those stream miles are located on National Forest System lands, making the Forest Service the single largest manager of critical habitat for these species.

The Forest Service, as well as other land managers and partners, are working to undo the legacy of past forest management practices through a variety of actions. Many of the logging roads in the vast network created on National Forest System lands are no longer needed. Road decommissioning can improve water quality and aquatic habitat by removing culverts and reducing erosion and stream sedimentation. Where roads are still needed, culverts and Aquatic Organism Passage (AOPs) are being upgraded to restore habitat connectivity. For example, removing and replacing round pipe culverts with designs like ‘bottomless arch’ culverts maintains the integrity of the stream bed, eliminates scour pools, and provides deeper and slower water for fish passage as well as dry passage for other animals. Upgraded AOPs often also reduce the risk of barrier failure during flood events, making road systems more resilient to climate change, which is expected to worsen flooding in the Pacific Northwest. Other streamflow restoration activities include including beaver dam analogs (BDAs) and alluvial water storage projects, which aim to replace and reconstruct woody debris in streams to mimic the function of natural beaver dams or other natural water storage infrastructure. Restoration work is happening alongside waterways as well: riparian vegetation treatments, which might include thinning, burning and/or replanting native vegetation can improve habitat for beavers and other riparian dependent species. Complexity is key to riparian systems, and some are fire-adapted, so the return of fire to the system may benefit salmon and other aquatic species by cooling summer stream temperatures and contributing to the presence of large wood in streams.

Much work remains to be done. In 2019, the Forest Service estimated that there were more than 3,600 fish barriers in perennial streams in the region, but in the prior decade, an average of only 40 barriers per year had been fixed. In order to increase the efficiency of planning aquatic restoration projects, the Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Regional Office signed a Decision in 2019 on a Regional Aquatic Restoration Project, which authorized 1,800 proposed aquatic restoration activities within riparian reserves across 17 National Forests in Oregon and Washington. The Decision covers a wide array of project activities intended to restore aquatic ecosystems and promote water quality: fish barrier removal, stream channel reconstruction, beaver dam analogs (BDAs), riparian vegetation treatments, and the reintroduction of low and moderate severity fire. The Regional Aquatic Restoration Project does not cover all types of aquatic restoration–many still must go through a separate NEPA permitting process–but it is a huge step in accelerating the pace of aquatic restoration.

It’s clear that forest management practices upslope and upstream have huge impacts on rivers, streams, and aquatic ecosystems. But there is growing evidence that the health of these aquatic ecosystems may have impacts on forest health and fire risk as well. Floodplain and wet meadow restoration can act as natural fuel breaks to better manage wildfires and can even aid in post-fire restoration by increasing capture of sediment from burned slopes. Stream and floodplain restoration also has the potential to not only reduce flood risk, but also promote variation in fire effects, or “pyrodiversity,” and in turn biodiversity, as fires burn less intensely in wet floodplains. Healthy salmon runs deliver nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus to higher reaches in the watershed, contributing to faster growth rates of riparian forests and streamside vegetation. Restored aquatic and riparian systems contribute to the overall connectivity and complexity of habitat within landscapes: many species don’t recognize ecosystem boundaries and will benefit from “ridgetop to valley bottom” approaches to restoration.

The opportunity for significant progress on aquatic restoration in the Pacific Northwest is immense, especially as recent legislation has increased available federal funding. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law created the new National Culvert Removal, Replacement & Restoration Grants Program, which has more than $1 billion available for state, local, and Tribal governments for culvert removal. It also directed $25 million to the first round of the new Collaborative Aquatic Landscape Restoration program and infused more than $40 million into the existing Legacy Roads and Trails program for FY22 projects. Even with these new investments, partnerships and collaborations are essential to delivering the capacity needed to implement this important work.

Blue Forest and its partners are deeply involved in efforts to restore aquatic ecosystems across not only the Pacific Northwest, but also the western United States. As part of the recently launched Rogue Valley I FRB, Blue Forest is supporting the Lomakatsi Restoration Project to implement about 100 acres of riparian restoration on the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest in Oregon with Tribal and Latinx crews. In the Snoquera restoration project, the Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Trout Unlimited, Conservation Northwest, South Puget Sound Salmon Enhancement Group, and other partners are working together to improve water quality and aquatic habitat in the Lower Greenwater River watershed in King and Pierce Counties, Washington. On the east side of the Cascades, Blue Forest is working with the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest and Chelan County on a Forest Resilience Bond to support implementation of the Upper Wenatchee Pilot Project, a landscape-scale project with both fire risk reduction and aquatic restoration goals. Blue Forest is also working with Pheasants Forever, Anabranch Solutions, and Utah State University to explore conservation finance opportunities for riverscape restoration on private lands in southeastern Oregon and in the Bear River watershed in Utah and Idaho.

Forest management practices have the power to either degrade or restore aquatic and riparian ecosystems, but healthy aquatic and riparian ecosystems also benefit forest health and resilience. Understanding the interconnectedness of these systems and the legacies of management practices that created the conditions of today is critical for working towards healthy and resilient landscapes that will benefit ecosystems and communities. With collaboration, dedication, and innovation, the next chapter in the history of forests and waterways will be a better one.