Building Trust and Resilience: The New Science Behind Carbon Credits from Fire Adapted Forests

Cover figure from Hurteau et al. 2024, doi:10.1002/fee.2801

Written by: Kirsten Hodgson, Senior Science Communications Associate

From supplying water and providing recreational opportunities, to sequestering and storing carbon, healthy forests provide essential ecosystem services to communities. But their ability to do so is increasingly threatened by factors like land use and environmental change, which decrease forests’ function and resilience and may even lead to their loss. Addressing this trajectory demands restoration at a pace and scale that outpace current funding structures. A new suite of research published in 2025 points to a promising path forward: strategically placed treatments in high-risk wildfire zones can reduce the probability of forest loss, deliver carbon storage and other ecosystem service benefits, and leverage those carbon benefits to pay for the work itself through the Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM).

Treated forests store carbon more securely

Forests that experience disproportionately high amounts of severe wildfire release their stored carbon and may not effectively store carbon again. When high severity wildfire burns through entire forest stands, it can raze landscapes and leave large dead patches while damaging soil quality and the seed bank, sometimes leading to forest loss as dead trees are replaced by grassland or shrubs. When soil and vegetation burn, large amounts of carbon are released into the atmosphere, ultimately contributing to rising temperatures and weather variability. In the past decade, forest fires have become a key driver of the declining status of global forests as a carbon sink. In fact, in much of California’s Sierra Nevada, forests have emitted more carbon per year than they have sequestered. Similarly, forests’ ability to provide other ecosystem services — like clean and reliable water, pollination and habitat for biodiversity, and access to recreation — is reduced by catastrophic wildfire.

On the other hand, resilient forests can contribute to carbon sequestration by fostering the growth of long-term, stable carbon stocks. Trees in resilient forests are less likely to burn during wildfires. Much of the carbon stored in resilient forests is therefore maintained on the landscape for decades or centuries, rather than released into the atmosphere during high-severity, high-mortality fires.

Ecological forest management practices are widely accepted as a means of increasing the resilience of forests to wildfire and improving the heterogeneity of fire effects on the landscape, protecting forests, animals, and communities from the devastation of unnaturally severe wildfire. However, the carbon benefits of ecological forest management in fire-adapted forests have been difficult to quantify, slowing the development of the VCM in these landscapes. Further, levels of trust in the VCM have suffered from lack of transparency and the use of methodologies that can overestimate project impact.

A suite of research published in 2025 by scientists at Blue Forest alongside partners at Vibrant Planet, American Forest Foundation (AFF), Northern Arizona University, and others illustrated reliable and transparent carbon quantification methodologies and applied these methods to quantify the carbon benefits of ecological forest management. Together, these papers demonstrate how these methods can better capture the carbon impacts of forest restoration compared to previous methods, provide a case study of their use in modeled and observed contexts, and begin to operationalize their adoption in carbon credit protocols.

Rigorous baseline methodologies are needed to build trust in the Voluntary Carbon Markets

In “Restoring credibility in carbon offsets through systematic ex post evaluation”, published in Nature Sustainability in July 2025, a team of authors led by INRAE’s Dr. Philippe Delacote — including Blue Forest’s Dr. Micah Elias and Vibrant Planet’s Dr. Katharyn Duffy — explains how reliance on predicted counterfactual baselines has eroded trust in forest restoration carbon credits and other nature based carbon projects. Predicted baselines are those where the “baseline” level of carbon emissions is calculated based on the initial conditions before a project, and does not change over time as the project proceeds. Because these baselines don’t account for the occurrence of unpredictable factors like policy change, new economic situations, or natural disasters like fires that impact a landscape’s carbon balance, they often inaccurately estimate the carbon impacts of forest projects.

The authors call instead for a transition to the use of annually updating, observed baselines, calculated based on observed changes in a reference region over time, while also highlighting the importance of transparency and increased rigor for rebuilding trust in the carbon market. Observed baselines are technically intensive to create and come with higher costs and greater risks for carbon credit project developers, but are critical to increasing the integrity of the carbon market. The VCM needs trustworthy carbon credits to maintain currency and utility. “A dynamic, observed baseline is more than a methodology — it’s a trust-building mechanism,” says Dr. Duffy. “It aligns carbon crediting with the way forests actually change, burn, and recover over time, dramatically improving the accuracy and transparency of reported benefits. When the market can see that improvement clearly, it unlocks confidence, investment, and scale for the kind of restoration work that landscapes urgently need.” Other papers published in 2025 by Blue Forest and collaborators have begun to provide actionable methods for observed baselines for carbon credit calculation, by applying these methods in modeled and observed scenarios to calculate the carbon benefits of forest restoration.

The carbon benefits of treatment could help forest restoration pay for itself

In January 2025, Dr. Micah Elias and coauthors published “Carbon finance for forest resilience in California” in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. This paper utilizes a modeling approach informed by observed baseline methodologies to estimate the carbon outcomes of thinning followed by prescribed burning in California’s Sierra Nevada. Despite an initial carbon cost, the results show that these forest restoration practices ultimately increase forest carbon storage and reduce carbon emissions compared to a modeled future without treatment. Starting nine years after treatment, forest stands rebound and begin to accumulate carbon at a rate of 3-6 tons of CO2 per year, for a total carbon benefit of 35 tons of CO2 per acre of treatment by the end of the 25-year modeling period. This carbon benefit stems from the shift — created by forest restoration treatments — of carbon storage from small, uniformly distributed plants across a landscape to larger, more spaced out trees that are more resilient to wildfire and less likely to burn. Additionally, these treatments reduce flame length by 78% five years post-treatment, meaning that fires that do occur are less severe and pose less threat to the remaining large trees, securing the carbon stored in them. When paired with additional carbon benefits from diverting woody byproducts of forest restoration into market-ready biomass utilization pathways, forest restoration could generate up to $6,100 per acre of carbon revenue. With current per-acre restoration costs ranging from $2,000 to $4,000, the revenue from these carbon benefits may allow forest restoration in some areas to pay for itself. “Now that we know the potential, we need to scale the science into actionable tools. That means building new market mechanisms and strengthening existing market mechanisms,” says Dr. Elias. “Building these scientific tools will enable us to leverage carbon markets to support community and landscape resilience.”

Observed treatment impacts support modeled findings

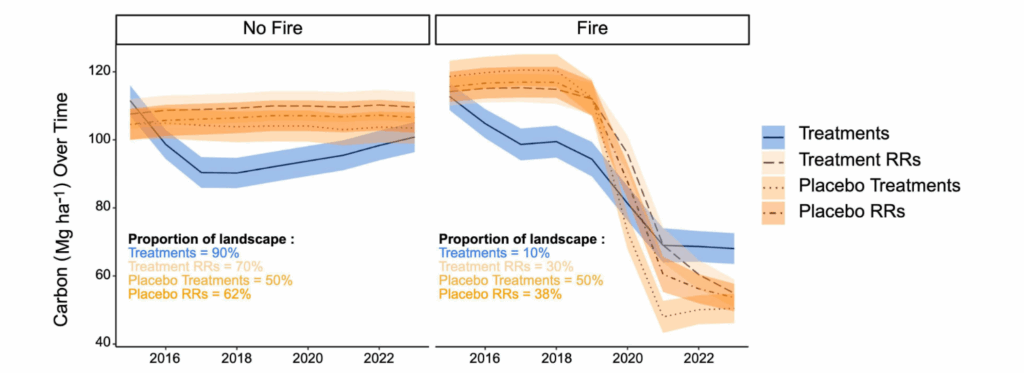

A group of authors led by AFF’s Ethan Yackulic published “Rising from the ashes: treatments stabilize carbon storage in California’s frequent-fire forests” in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change in September 2025. This paper applies observed carbon baselines to real landscapes in the Sierra Nevada treated in 2016 and monitors their performance through 2023, providing an ex-post companion to the earlier, modeling-based approach. The findings of this paper suggest that the benefits of forest restoration may be greater than some of those found using a modeled approach: treatments reduced the prevalence of high-severity fire by 88%, and treated plots rebounded and began to accumulate carbon with a total storage benefit of 18 tons of CO2 per acre by year seven post-treatment.

“Even though the treatments we monitored had a high initial carbon cost in the removal of live trees, our team saw a dramatic signal of forest resilience emerge in subsequent years,” said Yackulic. “While other studies have shown that management interventions reduce wildfire risk, it was encouraging to witness durable carbon storage at a landscape scale.” Treated areas even continued to sequester and retain carbon during the 2020 drought, while carbon levels remained stable or declined in untreated plots (Figure 1). The observed baseline and carbon benefit calculation methods used in this research are aligned with the methodology of a forthcoming dynamic baseline protocol from Verra, demonstrating how these methods can be operationalized to improve carbon accounting in the carbon market.

Figure 1. Carbon storage over time in treated and untreated pixels that experienced fire or no fire during the course of the study.

Increasing trust opens doors for ecosystem service-based payments for forest restoration

The better we get at quantifying carbon sequestration and storage benefits from forest restoration, the more market participants will trust the credits generated from this work, increasing available financing for initial and maintained forest restoration through carbon credits. This improvement of methods leads to alignment with the highest quality segment of the carbon market and increases transparency, increasing trust. It also opens avenues to new funding for forest restoration and, importantly, better dovetails wildfire resilience with climate initiatives, which to date have not been thoughtfully aligned. Ultimately, this advancement in methods allows for the integration of carbon into the growing suite of forest restoration benefits that are understood more deeply, allowing us to communicate about them with stakeholders and monetize them to invite new kinds of payors into landscape resilience.